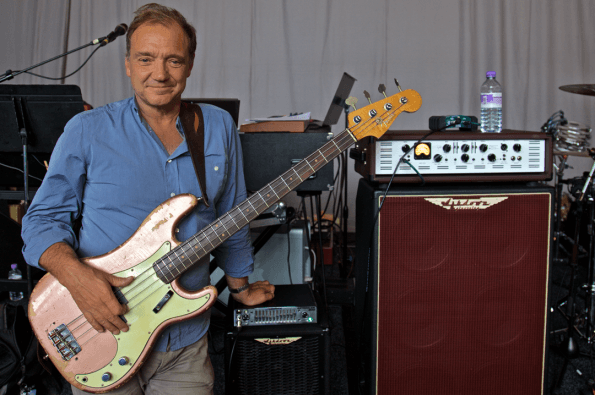

From all of us at A Fleeting Glimpse we want to send Guy Pratt our very best wishes and hope he has a great day celebrating his 56th Birthday.

From all of us at A Fleeting Glimpse we want to send Guy Pratt our very best wishes and hope he has a great day celebrating his 56th Birthday.

Category Archives: News

Nick Mason : Brian Johnsons Life On The Road

Please Note : The content of this page has been removed due to technical reasons.

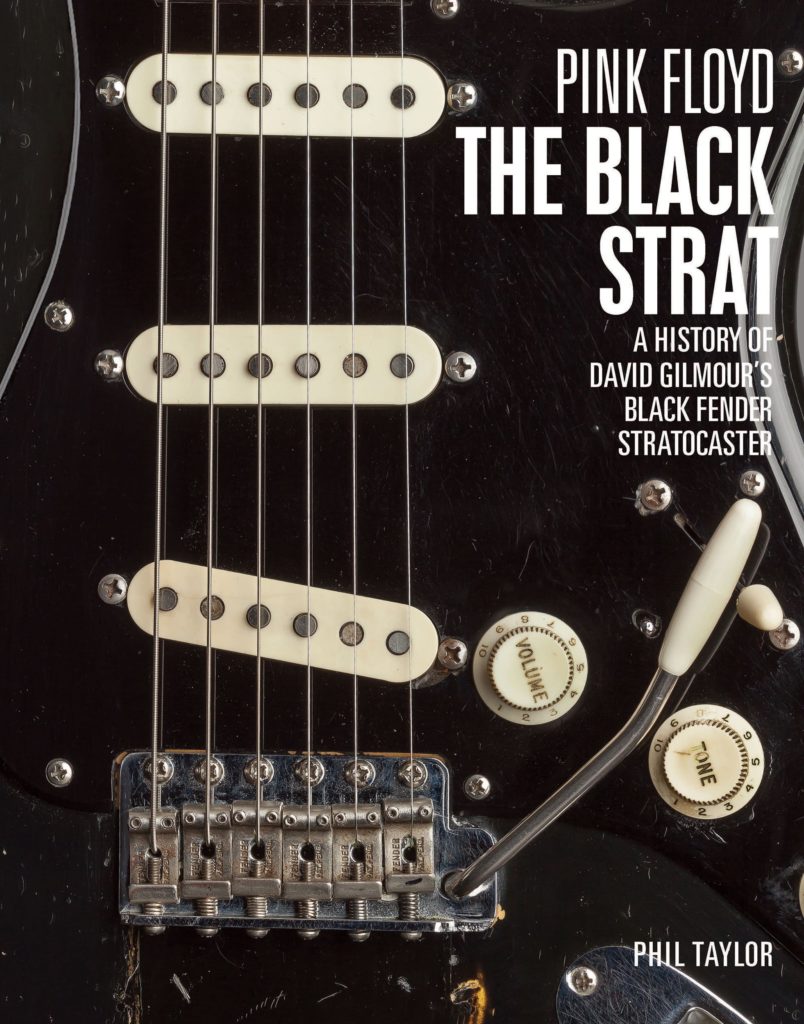

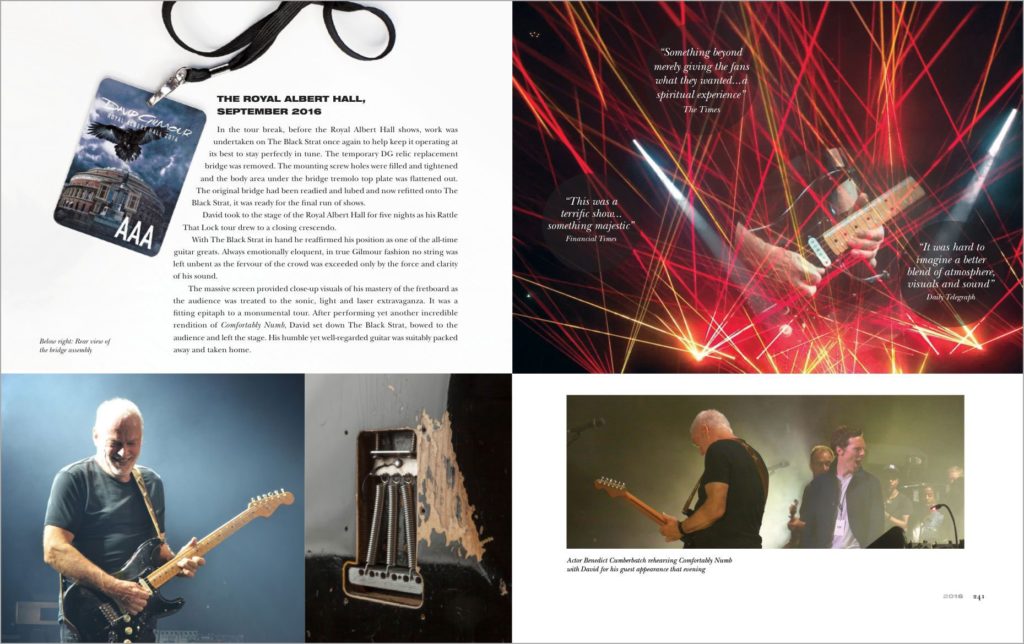

Phil Taylor : The Black Strat (Fourth Edition) Released 2017

This is his authorised listing from Amazon for the new updated fourth edition. With 56 new pages offering an ‘Access All Areas‘ pass to see behind the scenes of rehearsals, equipment and technical information.

The book contains over 400 photographs and diagrams within its 252 pages, many personal and previously unpublished in a chronological journey from 1970 to 2017.

It explores the phenomenal life of The Black Strat, David Gilmour’s favourite iconic and legendary black Fender Stratocaster.

This new large format 2017 edition, published to accompany the V&A exhibition ‘Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains‘, offers a rare insight into the world of David Gilmour’s quintessential guitar.

The music created with this humble Strat has entered into the homes and lives of quite literally billions of people.The Black Strat is a rewarding, accessible and superbly produced book that all Pink Floyd fans will thoroughly enjoy.

The Black Strat has featured on Pink Floyd tours and iconic albums including: Atom Heart Mother, Meddle, Obscured By Clouds, The Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals, The Wall, The Final Cut, The Endless River – on the film Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii and at the Pink Floyd reunion with Roger Waters for Live 8.

The Black Strat has featured on Pink Floyd tours and iconic albums including: Atom Heart Mother, Meddle, Obscured By Clouds, The Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals, The Wall, The Final Cut, The Endless River – on the film Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii and at the Pink Floyd reunion with Roger Waters for Live 8.

It has also appeared on David’s solo tours and projects: David Gilmour, About Face, On An Island, Remember That Night, Live in Gdánsk, Rattle That Lock and David Gilmour Live At Pompeii.

David has played it with many special guests including Jeff Beck, David Bowie, Paul McCartney, Kate Bush, Brian Ferry, Benedict Cumberbatch and many more.

A must read for any serious Pink Floyd fan. A must for all Pink Floyd fans.

The Book is available in small quantities on Amazon using the search term “Pink Floyd: THE BLACK STRAT – A History of David Gilmour’s Black Fender Stratocaster – Fourth Edition”

Please Note : A Fleeting Glimpse does not receive any funding at all, Donations are most welcome or you can support this site by using our sponsors links. This is especially true with Amazon, If you wish to purchase ANYTHING from Amazon, please use our special links.

USA | UK | CANADA Thanks!

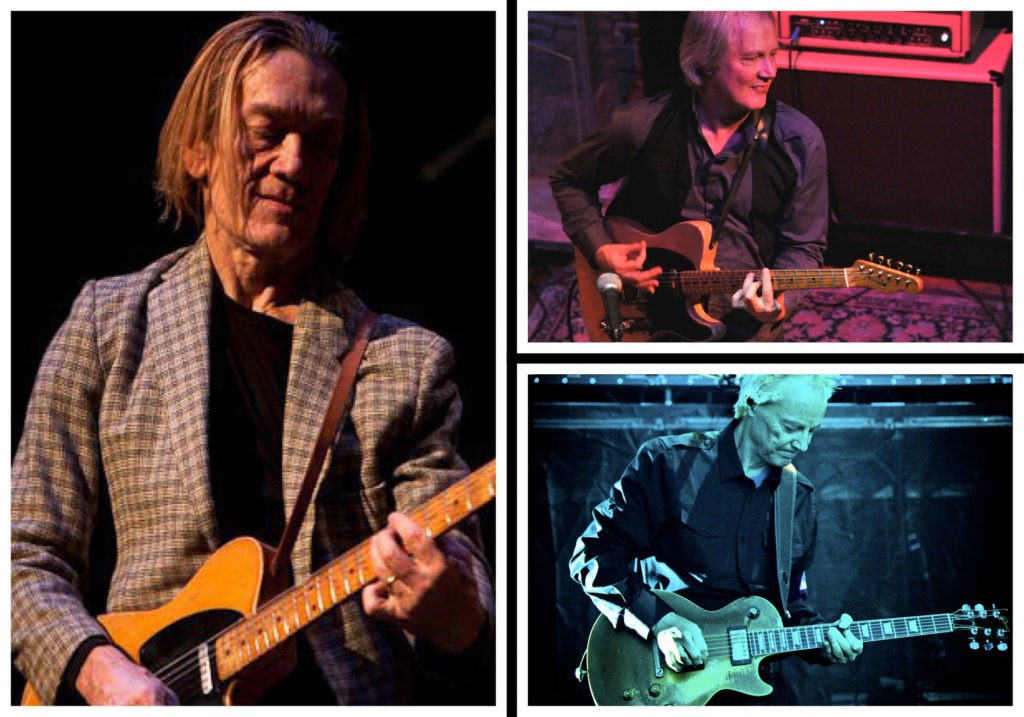

Snowy White : Announces 2 Blues USA Shows With GE Smith

FEATURING: Jim Weider (The Band), G.E. Smith (SNL Musical Director / Bob Dylan / Hall & Oates), Snowy White (Pink Floyd / Thin Lizzy)

G.E. Smith is currently a world renowned and in demand rock guitarist. Millions watched him front the Saturday Night Live Band weekly. He successful career includes recording and touring with the likes of Hall & Oates, playing on albums for Mick Jagger and David Bowie and helping compose the Wayne’s World theme song.

Jim Weider has built an international reputation performing with Bob Dylan, The Band, Hot Tuna, Keith Richards, Los Lobos, Dr. John, Paul Butterfield and more plus he fronts ProJECT PERCoLAToR and cofounded The Weight.

Terence Charles “Snowy” White is an English guitarist, known for having played with Thin Lizzy and with Pink Floyd as a backing guitarist, and more recently, for Roger Waters’ band.

“With three of the most prolific rock guitarists in the world, this is sure to be a historic night of blues, roots, and rock n roll. Each with their own notable career and accomplishments, this trio comes together to play tunes from Roy Buchanan, Little Richard, Steely Dan, Lee Dorsey, Sam Cooke, and more. Rounding out the all star rhythm section are Lincoln Schleifer on bass and Connecticut drummer Josh Dion (Buddy Guy, Los Lonely Boys, Eric Johnson)”

You can catch the shows which take place on

Jan 19th – Fairfield Theatre, Connecticut – (Tickets On Sale Now) – Click Here To Purchase Online

Jan 20th – Patchogue Theatre, Long Island – (Tickets On Sale Now) – Click Here To Purchase Online

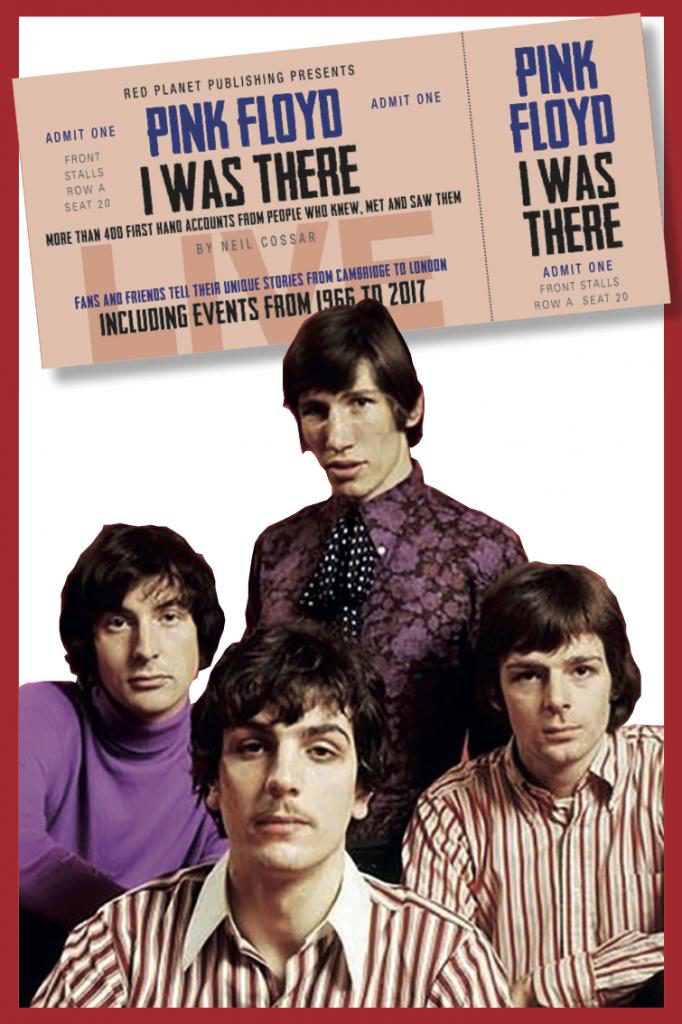

Pink Floyd – I Was There – New Book Release By Richard Houghton

A book containing over 350 fan memories of seeing Pink Floyd live has been published.

A book containing over 350 fan memories of seeing Pink Floyd live has been published.

Collated and edited by music writer Richard Houghton, ‘Pink Floyd – I Was There’ comprises memories of the band in action going back to their earliest days in the Swinging Sixties.

Richard, who has compiled similar anthologies on The Who and the Rolling Stones, said: ‘The book is a slightly different take on the history of Pink Floyd, as it’s trying to tell their story as a live act in the words of people who witnessed them in performance. It includes gig memories from the UFO Club and before, and is bang up to date with memories of Roger’s Us+Them tour. Hopefully it captures people’s memories faithfully and will give those who were there fond memories and those who weren’t a sense of what it was like.’

Richard is now working on a similar book about Jimi Hendrix but is still keen to hear people’s Pink Floyd memories. He said: ‘I’ve had several people share Floyd stories with me since the book went to print and so I’m collecting material for a possible volume two.’

Pink Floyd – I Was There is available to buy online direct from Red Planet Zone by clicking here.

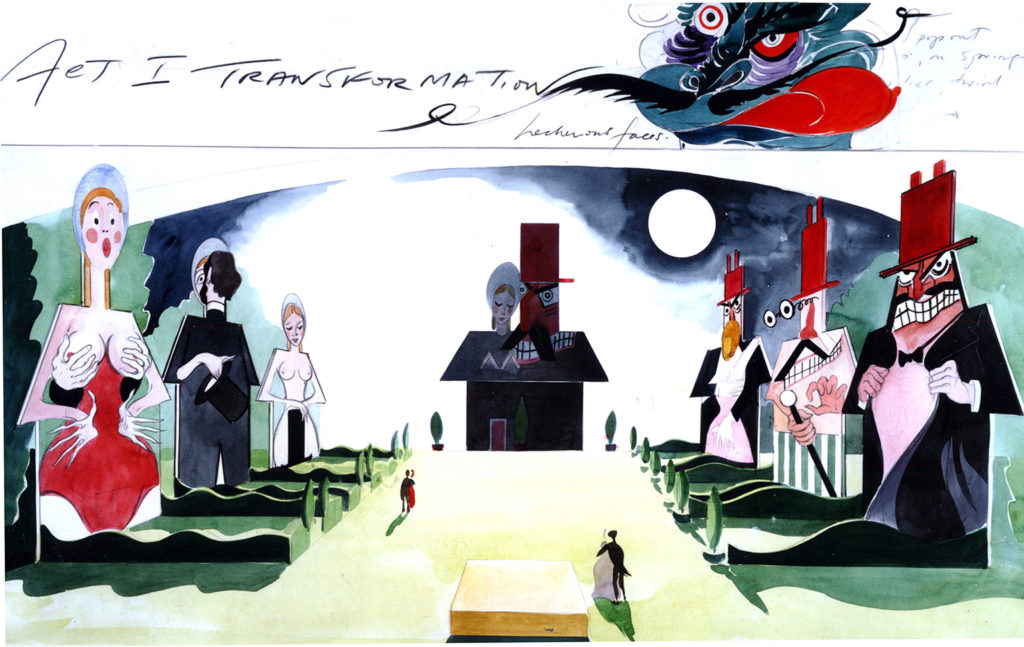

Gerald Scarfe : Stage & Screen Exhibition At London’s House Of Illustration

You’re likely to recognise the satirical cartoons of Gerald Scarfe from his work with Pink Floyd, but you might be surprised to discover his lesser-known production designs for the stage and screen.

You’re likely to recognise the satirical cartoons of Gerald Scarfe from his work with Pink Floyd, but you might be surprised to discover his lesser-known production designs for the stage and screen.

Having enjoyed a long career as a political cartoonist, starting out in the pages of Punch and Private Eye and then embarking on a 40-year relationship with the Sunday Times, Scarfe has also devised sets, concepts and characters across film, opera, ballet and theatre.

London’s House of Illustration offers a rare opportunity to explore Scarfe’s extensive work in these areas, presenting storyboards, costumes and props from a range of projects including Disney’s Hercules and Pink Floyd’s The Wall (for which Scarfe designed the animation sequences).

The artist’s typically acerbic imagination and vibrant style are evident throughout, as well as his desire to ‘bring my creations to life – to bring them off the page and give them flesh and blood, movement and drama.’

The Exhibition is currently running until the 21st January 2018 at London’s House of Illustration, 2 Granary Square, King’s Cross London N1C 4BH,

R.I.P Iggy The Eskimo

The former girlfriend of original Pink Floyd frontman Syd Barrett, Evelyn “Iggy” Rose died peacefully on the December 13, 2017.

She was 69 years old. Rumored to be part Inuit, Rose was nicknamed ‘Iggy the Eskimo.’

She also had the distinction of being the nude woman pictured on Barrett’s 1970 album, The Madcap Laughs.

Roger Waters : Us And Them 2018 Tour Dates (More Shows Announced)

After 63 sold out shows in the U.S. and Canada in 2017, we are excited to announce further shows for 2018

After 63 sold out shows in the U.S. and Canada in 2017, we are excited to announce further shows for 2018

New Dates Added 12/12/17 !! (New Additions In Red)

January 24th – Spark Arena, Auckland, New Zealand

January 26th – Spark Arena, Auckland, New Zealand

January 30th – Forsyth Barr Stadium, Dunedin, New Zealand

February 2nd – Qudos Bank Arena, Sydney Olympic Park, Nsw, Australia

February 3rd – Qudos Bank Arena, Sydney Olympic Park, Nsw, Australia

February 6th – Brisbane Entertainment Centre, Boondall, Qld, Australia

February 7th – Brisbane Entertainment Centre, Boondall, Qld, Australia

February 10th – Rod Laver Arena, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

February 11th – Rod Laver Arena, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

February 16th – Adelaine Entertainment Centre, Hindmarsh, Sa, Australia

February 20th – Perth Arena, Perth, Wa, Australia

April 13th – Palau Sant Jordi, Barcelona, Spain

April 14th – Palau Sant Jordi, Barcelona, Spain

April 17th – Mediolandum Forum Di Assago, Milan, Italy

April 18th – Mediolanum Forum Di Assago, Milan, Italy

April 21st – Unipol Arena, Bologna, Italy

April 22nd – Unipol Arena, Bologna, Italy

April 24th – Unipol Arena, Bologna, Italy

April 25th – Unipol Arena, Bologna, Italy

April 27th – O2 Arena, Prague, Czech Republic

April 28th – O2 Arena, Prague, Czech Republic

May 2nd – Papp Laszlo Budapest Sportarena, Budapest, Hungary

May 4th – Arena Armeec, Sofia, Bulgaria

May 6th – Arena Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

May 9th – Halle Tony Garnier, Lyon, France

May 11th – Sportpaleis, Antwerp, Belgium

May 14th – Barclaycard Arena, Hamburg, Germany

May 16th – Stadhalle, Vienna, Austria

May 20th – Meo Arena, Lisbon, Portugal

May 21st – Meo Arena, Lisbon, Portugal

May 24th – Wizink Center, Madrid, Spain

May 25th – Wizink Center, Madrid, Spain

May 28th – Hallenstadion, Zurich, Switzerland

May 29th – Hallenstadion, Zurich, Switzerland

June 1st – Mercedes-Benz Arena, Berlin, Germany

June 2nd – Mercedes-Benz Arena, Berlin, Germany

June 4th – Sap Arena, Mannheim, Germany

June 8th – U Arena De Nanterre, La Defense, Paris, France

June 11th – Lanxess Arena, Cologne, Germany

June 13th – Olympiahalle, Munich, Germany

June 16th – Stade Pierre Mauoroy, Villeneuve D’Ascq, Lille, France

June 18th – Ziggo Dome, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

June 19th – Ziggo Dome, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

June 22nd – Ziggo Dome, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

June 23rd – Ziggo Dome, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

June 26th – 3Arena, Dublin, Ireland

June 27th – 3Arena, Dublin, Ireland

June 29th – SSE Hydro, Glasgow, Scotland

June 30th – SSE Hydro, Glasgow, Scotland

July 2nd – Echo Arena, Liverpool, England

July 3rd – Manchester Arena, Manchester, England

July 6th – Hyde Park, London, England (Barclays Festival)

July 7th – Birmingham Arena, Birmingham, England

June 8th – U Arena De Nanterre, La Defense, Paris

June 9th – U Arena De Nanterre, La Defense, Paris

July 11th – Mura Storiche, Lucca, Italy (Lucca Summer Festival)

July 14th – Circo Massimo, Rome, Italy (Rock In Roma 2018)

August 3rd – Tauron Arena Krakow, Krakow, Poland

August 5th – Ergo Arena, Gdansk, Poland

August 7th – Jyske Bank Boxen, Herning, Denmark

August 10th – Royal Arena, Copenhagen, Denmark

August 11th – Royal Arena, Copenhagen, Denmark

August 14th – Telenor Arena, Oslo, Norway

August 15th – Telenor Arena, Oslo, Norway

August 18th – Friends Arena, Stockholm, Sweden

August 21st – Hartwell Arena, Helsinki, Finland

August 24th – Arena Riga, Riga, Latvia

August 26th – Zalgaria Arena, Kanuas, Lithuania

August 29th – Skk Arena, St Petersburg, Russia

August 31st – Olympiski, Moscow, Russia

October 9th – Allianz Parque, Sao Paulo, Brazil

October 13th – Estadio Nacional Mane Garricha, Brasillia, Brazil

October 17th – Itaipava Arena Fonte Nova, Salvador, Brazil

October 21st – Estadio Do Mineirao, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

October 24th – Estadio Do Maracana, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

October 27th – Estadio Couto Pereira, Curitiba, Brazil

October 30th – Estadio Beira-Rio, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil

November 3rd – Estadio Centenario, Montevideo, Uruguay

November 6th – Estadio Unico De La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina

November 14th – Estadio Nacional. Santiago Chile

November 17th – Lima, Peru (TBD)

Our 2018 Tour Zone will be open for business very shortly !!

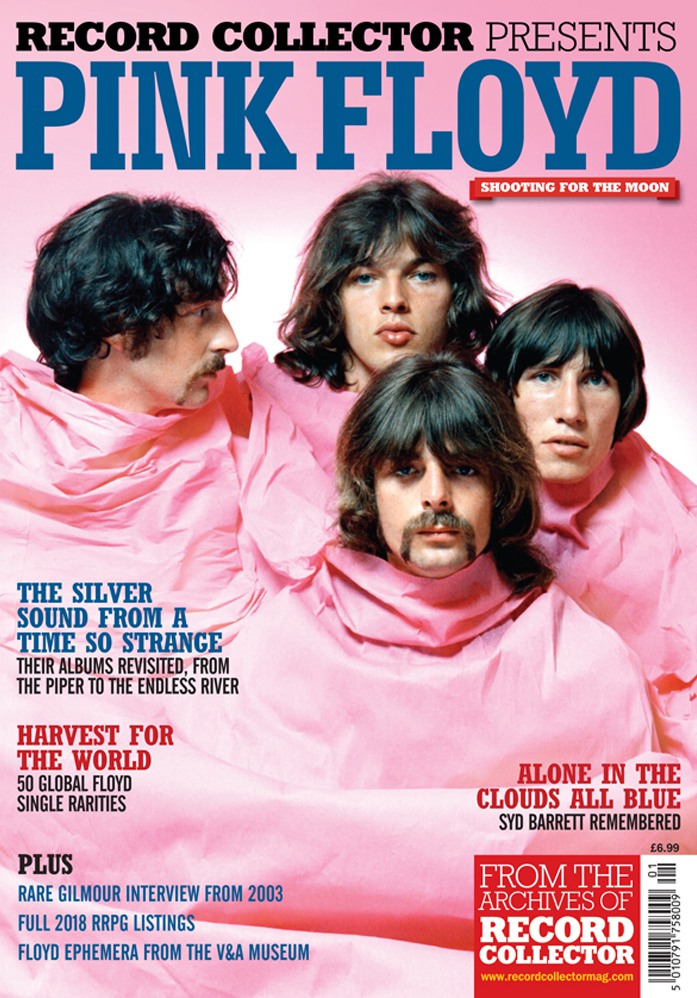

Pink Floyd : Record Collector Magazine Presents Pink Floyd Special Edition

Now available in UK stores is a special edition of Record Collector Magazine, completely focused on Pink Floyd. With the sub title of Shooting For The Moon, the magazine brings together both old and new from the long-running, respected publication.

Now available in UK stores is a special edition of Record Collector Magazine, completely focused on Pink Floyd. With the sub title of Shooting For The Moon, the magazine brings together both old and new from the long-running, respected publication.

Pink Floyd – Shooting for the Moon vividly traces the development of this globally adored band, from their heady psychedelic beginnings at the pulsating heart of London’s underground music scene in 1967 to their undying status as rock divinities half a century later. This 116-page bookazine combines the most fascinating and vital coverage from Record Collector’s Pink Floyd archive with freshly commissioned articles from David Quantick, Kris Needs, Daryl Easlea and Oregano Rathbone, featuring in-depth profiles of each album, a thorough delve into the band’s solo output and a celebration of their status as an unparalleled live spectacle.

As well as the finest rock’n’roll writing, Pink Floyd – Shooting for the Moon includes rare photographs and a full UK discography with single, EP and album values from the 2018 edition of The Rare Record Price Guide.

You can purchase the issue online now from the magazines official online store by clicking here

For those not wishing to buy online you can find it on the shelves of most major UK news and shopping retailers

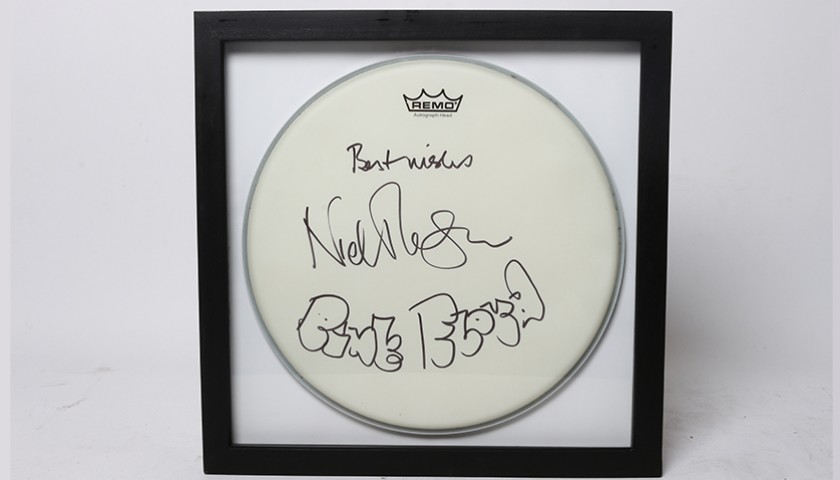

Nick Mason – Pink Floyd Drummer Auctions Off Drum Head In Aid Of Teenage Cancer Trust

Visitors may be aware of the charity Teenage Cancer Trust in which David Gilmour played a fundraising concert at The Royal Albert Hall early on in 2016, This time however it is Nick Mason that is providing his support in a way that you too can also help.

Visitors may be aware of the charity Teenage Cancer Trust in which David Gilmour played a fundraising concert at The Royal Albert Hall early on in 2016, This time however it is Nick Mason that is providing his support in a way that you too can also help.

Teenage Cancer Trust makes sure the seven young people aged 13 to 24 diagnosed with cancer every day don’t face it alone. They help young people and their families deal with the many ways cancer affects your body, mind and life. They work in partnership with the NHS, providing expert staff and specialist units in Principal Treatment Centres for cancer and bring young people together so they can support each other.

They also give presentations in schools so young people understand more about cancer and go to the doctor earlier. And they help medical professionals and politicians understand why young people with cancer need specific support.

Almost half of young people with cancer are not treated in their units. Instead they are treated in hospitals where there isn’t the same level of expertise, and where they might never meet another young person with cancer. This is a scary and lonely experience, and it must change. They’re building a wider Nursing & Support Service within the NHS to help all young people, wherever they receive treatment.

The website www.CharityStars.com are currently running a set of auctions under the festive title of “12 Drummers Drumming” – a reference to the famous “12 Days of Christmas” song.

The auctions have been organized to raise awareness and raise funds to support the Teenage Cancer Trust charity, Included in the auctions are a range of drums, drum heads and sticks from a range of artists. These include Nick Mason, Zak Starkey (son of Ringo, and The Who’s drummer), Dave Grohl, and Nicko McBrain.

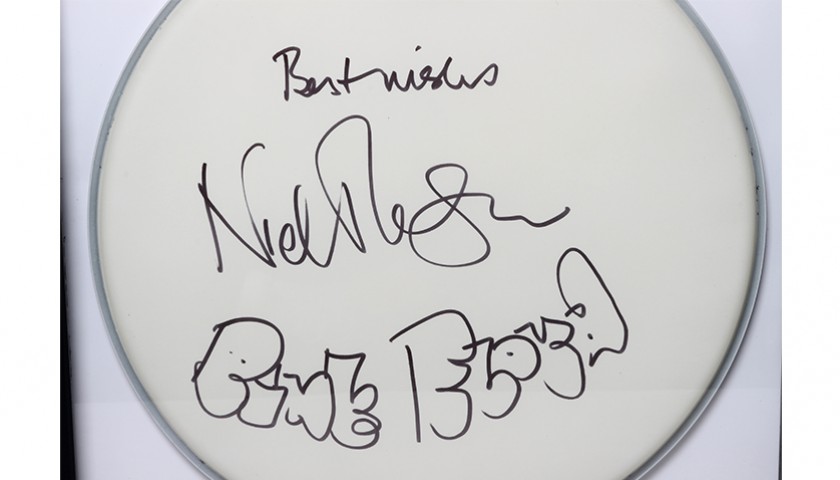

Nick Mason has kindly donated a framed drum head with the classic Pink Floyd “bubble” writing included in Nick’s dedication.

Nick Mason has kindly donated a framed drum head with the classic Pink Floyd “bubble” writing included in Nick’s dedication.

You can bid in the auction which can be seen by clicking here

The auction for this ends on December 13th 2017, at 4:00pm GMT.

You can also visit the Teenage Cancer Trust charity website for more information and to support them via donations, or purchasing items such as their music related goodies including David Gilmour concert posters/t-shirts.